From Croatia to Kosovo, people grapple with rising prices.

Since early 2020, when COVID-19 emerged, consumer prices in Kosovo have been steadily rising. Initially, pandemic-related restrictions disrupted global supply chains, driving up the cost of goods. This was followed by an energy crisis in 2021, further straining prices. Then, in 2022, the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine caused additional supply chain disruptions, exacerbating the situation.

According to the Kosovo Agency of Statistics (KAS), the average inflation rate for 2024 was 1.6%. While this inflation rate may seem low, it adds to the cumulative inflation of previous years. In 2023, the average inflation rate was 4.9%, and in 2022, it was 11.6%.

As a result, the prices of essential products today are significantly higher than in 2020.

Despite the continuous rise in prices over the past four years, aside from complaints on social media and in television news reports, there has been no structured mobilization — neither from the public nor, more importantly, from the government. That changed in February 2025. A group of people launched the Kosovo Boycotts movement, calling for a boycott of supermarket chains to put pressure for price reductions.

This initiative was inspired by a similar movement in Croatia, where the mobilization first began. People in Croatia, Kosovo and other Western Balkan countries are all feeling the impact of rising prices in their daily lives.

At the end of January, a mass mobilization began in Croatia, led by a consumer protection group known as Hey, inspectors. The group called for a boycott of supermarkets and other retailers to protest price increases. “People are urged not to buy anything on that day” said the group on social media, among other statements.

According to the European Union’s (EU) statistics office, Eurostat, in December, the average inflation rate in Croatia was 4.5%, highest in the eurozone. Inflation in Croatia caught the attention of both locals and tourists. Videos of tourists surprised at the rising prices went viral on social media.

The boycott mobilization in Croatia gained widespread support, with people reducing their purchases to essential items. This collective initiative led to a significant drop in retail sales; turnover fell by 44%, while the total value of sales dropped by 53% on the first Friday of the boycott, January 24. Photos of empty supermarkets circulated that day, creating a strong impact on people, sparking enthusiasm and sustained engagement for several weeks.

In response to the boycott, the Croatian government took measures to address people’s concerns. On January 30, Croatia’s Ministry of Economy announced that another 40 items would be added to the list of products subject to price freezes, to support the most vulnerable groups in society.

Price freezing is one way governments or market regulators can temporarily intervene to regulate markets in free economies. This measure sets a limit on the price a company can charge for a service or product. Such restrictions are typically used to protect consumers from inflated or excessive costs, particularly for essential goods and services such as energy, food or rent — especially in cases of market failure, crises or monopolistic behavior.

The success of the movement in Croatia inspired similar actions across the Balkans, with countries such as Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina organizing boycotts to protest high prices.

In North Macedonia, the boycott, which began on January 31, nearly halved daily sales, with an average drop of 46.29% across eight major supermarket chains compared to the previous day.

The government of North Macedonia also responded. On February 18, it introduced a price ceiling, capping profit margins for over 102 product groups, including over 1,000 food and non-food items.

According to the decision, the profit margin for basic products such as bread, flour, oil and eggs cannot exceed 5%. For 55 other products, including meat and canned goods, the margin is set at 10%, while for 39 additional products, such as fruits, vegetables and hygiene items, the profit margin is capped at 15%.

With ongoing boycotts, Croatia has also triggered a domino effect in Kosovo.

Kosovo boycotts

Amid the election campaign for the general elections held on February 9, social media in Kosovo was flooded with images of high-priced products. The boycott movement in Croatia gradually gained attention, and eventually, a group of people in Kosovo formalized their own call for a boycott through the Kosovo Boycotts initiative.

Redon Kuçi, a 20-year-old web and mobile applications student who also works as a manager at a textile company, is one of the movement’s nine initiators. Kuçi says the initiative was inspired by similar efforts in Croatia and Serbia, where boycotts led to significant price reductions.

“We saw that in neighboring countries, boycotts were successful, so we thought why not try it ourselves?” said Kuçi.

To mobilize the population, the initiative used a combination of social media platforms and physical campaigns. The initiative’s Facebook group, with over 9,200 members, has become a key space for exchanging ideas and information. People quickly began sharing evidence of deceptive discount pricing by supermarket chains in Kosovo and comparing prices with those in other European countries known for their higher cost of living.

“We have engaged with volunteers who have helped put up posters and stickers around the cities, which has helped spread the message to more people,” said Kuçi.

The initiative gained support from Consumer Defenders, a nongovernmental organization that advocates for consumer protection. Small local businesses have also backed the movement, viewing it as an opportunity to strengthen the local economy. The initiative encourages people to purchase supplies from small shops and local product vendors.

The first boycott was organized on February 10, the day after the parliamentary elections. With public discourse focused entirely on election debates, the boycott went largely unnoticed. According to data from the Tax Administration of Kosovo (TAK), turnover in large supermarkets dropped by around 100,000 euros compared to the previous Monday.

“This is an important indicator of the boycott’s impact,” says Kuçi, adding that participation could have been higher if the elections had not taken place the day before. However, a 100,000-euro drop in turnover for businesses that generate over 13 million euros daily can be considered a minimal effect of the call. For example, on February 3, stores recorded a turnover of approximately over 13.496 million euros, while on the day of the boycott, it was around 13.393 million euros.

If we draw a parallel with Croatia, where the boycott led to a 44% decrease in turnover and North Macedonia, where it dropped by 46%, in Kosovo, the decline did not even reach 1%.

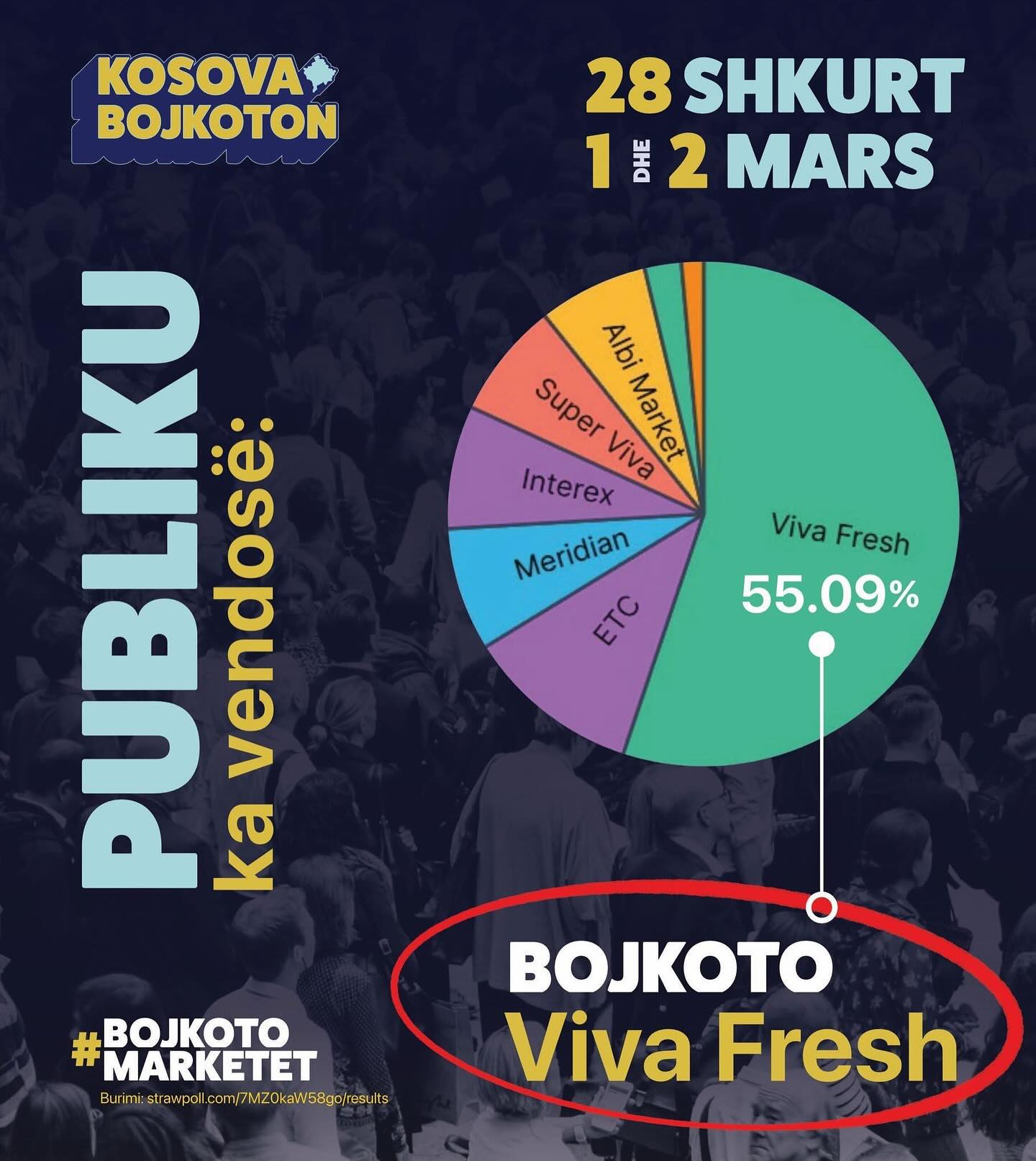

Noticing limited mobilization, the initiative has introduced a new approach. Since the end of February, it has focused on short-term boycotts of individual supermarket chains, rotating every few days.

The boycott calls will continue into March, shifting to a new supermarket chain. People participating in the Kosovo Boycotts group select the next target through a Facebook questionnaire.

Meanwhile, the organizers are preparing for a larger boycott. They have stated that they are coordinating with other groups in the region to organize a major regional boycott on March 15, International Consumer Day.

Consumption fills the state budget

Consumption plays a crucial role in Kosovo’s economy. It is one of the main sources of state revenue through the value-added tax applied to all basic products. This highlights not only the significance of consumption in the country’s economy but also the potential impact a broader boycott could have.

Blend Hasaj, executive director of the GAP Institute, says that food consumption is the main pool to which more than half of households’ annual income flows — money earned through work and remittances from the diaspora. However, he notes that despite rising product prices, people have continued to purchase the same amounts.

“In addition to the 3.1 billion euros paid as wages in our economy in 2024, more than 1.35 billion euros were received as remittances by families in Kosovo,” Hasaj said. “Inflexible consumer preferences [which remain unchanged despite price fluctuations], along with a steady trend of price increases in most years before the pandemic, have also played a role.”

Hasaj points out that, based on research conducted by the GAP Institute, other products, such as gas for cars, also have inelastic consumption — meaning that despite price increases, demand does not decrease. According to Hasaj, this is also the case with cigarettes and carbonated drinks.

In addition to these products, basic food items like flour, oil, dairy products, eggs, coffee, fruits and vegetables are also included. Since their purchase is essential, price increases have not deterred consumers. It is precisely these basic products that have experienced the most significant price hikes.

According to Kuçi from Kosovo Boycotts, some supermarkets have introduced temporary price reductions and short-term offers, which can be seen as a response to the pressure of the boycott.

“Our goal is to exert economic pressure on supermarkets to compel them to lower prices in a sustainable manner, not just temporarily in reaction to the boycott,” says Kuçi.

The price of products is determined by sellers, based on a combination of purchase costs, operating expenses, taxes and profit margins. Since the majority of consumer goods are imported from the region and the rest of Europe, exposure to high prices is expected to persist.

How much did prices increase since 2020?

• Tomatoes 117.6%.

• Fuels 34%,

• Firewood 38.8%,

• Potatoes 27.7%,

• Milk 41.4%,

• Beans 44.9%,

• White bread 45.7%,

• Peppers 54%,

• Chicken 56.3%

• Wheat flour 62%,

• Sugar 72.9%

Importing a product from one country to another incurs additional costs for sellers, as transportation and customs fees are included — ultimately raising the price consumers pay. According to numerous reports from people in the Kosovo Boycotts group and on social media, consumers in Kosovo pay more for similar products than those in Germany, where the average gross salary exceeds 4,000 euros. In contrast, according to KAS, the average gross salary in Kosovo in 2023 was 570 euros.

Such situations, particularly the high dependence on imports, highlight the importance of developing domestic production capacities. However, imports are not the only factor — some local producers have raised prices even when their products became more in demand due to the lack of imported goods.

One example of this is the ground biscuit market in Kosovo. Plazma biscuits could no longer be imported from Serbia after Kosovo’s government imposed a ban on Serbian goods in 2022. As a result, the price of a similar product produced in Kosovo increased.

This is a typical example of how prices are regulated based on the principle of supply and demand. In the case of biscuits imported from Serbia, the removal of this product from the market led to an increase in the price of a similar domestic product, which initially had the lowest price. With supply decreasing while demand remained unchanged, market prices adjusted accordingly.

The state response

Unlike the governments of Croatia and North Macedonia, which responded to the boycott initiative by imposing price caps or freezing prices, the Kosovo government has remained silent. Despite this, the organizers are determined to continue their efforts and are considering organizing more protests and boycotts to increase pressure.

As a group that is strengthening day-by-day, they have outlined a list of demands. According to Kuçi, these include the implementation of a law on price caps. The group demands long-term and sustainable price reductions from supermarkets, greater media and state involvement in exposing price manipulation and increased transparency about origin of products — particularly in distinguishing fruits, vegetables and meat. Furthermore, Kuçi emphasizes the need for greater support for local producers to reduce dependence on imports.

The Kosovo government attempted to implement a price ceiling as early as 2022 by adopting a law on temporary measures for basic products in special cases of destabilization. This law classified basic products as cereals, bread, flour, rice, pasta, sunflower oil, milk, table salt, chicken eggs, chicken meat, granulated sugar, personal hygiene products and firewood. However, in November 2022, the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK) challenged the law in the Constitutional Court, arguing that it created opportunities for government intervention in the free market.

In November 2023, the Constitutional Court of Kosovo declared several articles of this law unconstitutional. Contrary to public interpretation that the court struck down the entire law, it clarified that state intervention to protect consumers from price increases in specific cases of market destabilization is constitutional. The issue, according to the court, was the manner in which this intervention was proposed under the law.

Former president of Kosovo’s Constitutional Court, Gresa Caka-Nimani, later explained in a television interview on Klan Kosova that the law was overturned because it granted the minister and prime minister the authority to intervene in prices and regulate the free market. As a result, the court ruled that such powers should be delegated to an independent body or authority.

According to Hasaj from the GAP Institute, any interventions should be short-term.

“Temporary interventions with price caps, along with proportional and transparent decisions, could be an option in cases where the problem worsens. However, they should not be long-term, as they pose significant risks to the economy,” he said.

Setting price ceilings for an extended period can lead to market distortions. The balance between supply and demand may be disrupted, as regulated prices often stimulate increased demand, while supply may not be sufficient to meet it. As a result, this could lead to a halt in production as long as prices remain fixed. Another negative effect could be a decline in product quality, some producers might attempt to compensate for price limitations by unfairly increasing their profit margin.

Similarly, major interventions — such as those often proposed by politicians during pre-election periods — to reduce tax rates, including lowering the value-added tax on a wide range of products, could negatively impact the economy. According to Hasaj, this is because the state budget relies heavily on consumption as its primary source of revenue.

“They strain the public budget, making it difficult for the state to cover expenses for pensions, social schemes and public sector salaries,” Hasaj said. Meanwhile, he adds that the most vulnerable groups in society are the hardest hit by price increases. Therefore, if the government intervenes with other measures, they should be specifically targeted rather than applied uniformly.

The supermarket boycott is rooted in the basic principles of free-market economics. By reducing demand, it aims to put pressure on product prices with the expectation that they will decrease. In theory, a market with fewer buyers should reflect this shift in pricing.

However, this strategy carries a risk — if demand increases again after a period of boycott, prices may return to previous levels or even rise.

If the boycott succeeds in establishing a new standard of lower prices or influencing consumer behavior — such as encouraging shoppers to buy from small local stores — its impact could be more sustainable. Ultimately, the outcome depends on how market dynamics evolve and stabilize after the boycott.

Feature Image: Lum Hajrullahu / K2.0

Want to support our journalism?

At Kosovo 2.0, we strive to be a pillar of independent, high-quality journalism in an era where it’s increasingly challenging to maintain such standards and fearlessly pursue truth and accountability. To ensure our continued independence, we are introducing HIVE, our new membership model that offers an opportunity for anyone who values our journalism to contribute and become part of our mission.

Become a member of HIVE or consider making a donation.

- This story was originally written in Albanian.